Samuel Pierpont Langley

Before attempting a full-scale version, he built a quarter-size model which flew

successfully, the first time a gasoline engine had actually driven an airplane. In

October, 1903, he was ready for what he confidently believed would be the first sustained,

man carrying, heavier-than-air flight in history.

Of all the early trail blazers one of the most

controversial, and surely one of the most unlucky, was Samuel Pierpont Langley. This

distinguished astronomer, the director of the Smithsonian Institution, was well into his

fifties when the lure of the air gripped him. He began by making elastic band propelled

models based on Alphonse Penaud's little aircraft. Then, in 1889, a little aero

steam engine designed two decades earlier by John Stringfellow was presented to the

Smithsonian. Studying this historic curio, Langley realized that better steam engines

could be built and decided that he could build them.

In 1891 he constructed the first of his model "aerodromes,"

as he called them. The steel frame was too heavy; it would not fly. For the next five

years Langley doggedly kept building models, trying to solve the power-to-weight problem.

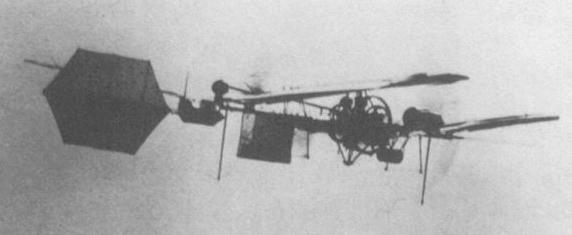

Finally, in 1896, he produced a steam-driven model--a sort of double monoplane with wings

set in tandem--that flew for three quarters of a mile and then came down only because the

fuel gave out.

Before attempting a full-scale version of the Langley Aerodrome, he

built a quarter-size model which flew successfully, the first time a gasoline engine had

actually driven an airplane. In October, 1903, he was ready for what he confidently

believed would be the first sustained, man carrying, heavier-than-air flight in history.

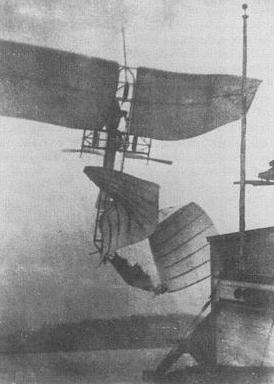

The newspapermen waved their hands. Manly looked down and smiled. Then

his face hardened as he braced himself for the flight, which might have in store for him

fame or death. The propeller wheels, a foot from his head, whirred around him one thousand

times to the minute. A man forward fired two skyrockets. There came an answering 'toot,

toot,' from the tugs. A mechanic stooped, cut the cable holding the catapult; there was a

roaring, grinding noise--and the Langley airship tumbled over the edge of the houseboat

and disappeared in the river, sixteen feet below. It simply slid into the water like a

handful of mortar.

A second attempt endeding in

failure that crushed even Langley's stalwart spirit. The press of the country, reflecting

the curious sadism with which crowds had greeted aeronautical failures since the days of

the Montgolfiers, broke into a chorus of jeers. Langley died a broken man in

February 1906. He was hurt not so much as his failure to achieve what the Wright

Brothers had done, but by the deluge of ridicule inflicted upon him by the press.

The Langley Aerdrome did finally fly when Glenn Curtiss rebuilt

the old Langley machine with slight modifications and flew it succesfully at Hammondsport

N.Y. in 1914. He flew this aircraft to weaken the position of the Wright Brothers

who had lodged a patent infringment lawsuit against Curtiss.